I do a lot of work in “branded content” – working with brands making films. Call them what you will, even when they’re great, and even when the brand truly cares about making a difference, or making some good entertainment, you can call them what they also are: advertisements. I can argue all day that if the filmmaker has creative control, it’s not much different than a commissioned piece for the BBC (I believe this to be true, but that’s another post), or one funded by MacArthur (again, I believe this to be true), but regardless, the clients I work with are pretty transparent about their relationship.

Every brand I work with prominently displays their logo at the beginning and often says “Brand X Presents…” so you know that what you’re about to watch is funded by a brand. In fact, we’re all proud of the films we sponsor, and we think they’re great films – that’s what we call them, films. You can quibble with how indie they are, but they’re good short or feature films that happen to be funded by a brand. Some call them films, some call them content, some call them branded films or branded content, but one thing we would never call them is journalism.

Apparently, the NYT doesn’t share this ethical standard. I awoke this morning to read the NYT in print (old habits die hard), and on the back page of the paper was a full page advertisement, congratulating themselves for the Cannes Lion Grand Prix for Mobile for their VR app, and Grand Prix for Entertainment (italics mine) for their VR film “The Displaced.” It closes:”Congratulations to all who were involved in bringing our journalism to a new frontier.” (italics mine again) Here’s a photo:

Ad/Journalism Awards

Journalism? I nearly puked up my breakfast. That’s the hocus pocus I’m referring to in the title, but let’s call it “virtual reality…” The Cannes Lions are awards specifically for advertising. Or as the NYT’s own Jim Rutenberg describes it in the next section: “On the surface, this festival is a great bacchanalia the advertising industry holds with its clients and business partners in Big Consumer Goods, Big Entertainment and Big Journalism.” Nothing celebrated there could remotely be called journalism. And neither the NYT VR app, or this film is either. The app may be used for journalism someday, but make no mistake, their plans for it are mainly for advertisers. That’s why the app’s description is under their marketing URL: http://www.nytimes.com/marketing/nytvr/

And in the case of The Displaced, while you’d have a hard time knowing it from the NYT itself, it is branded content. As Cannes Lion jury president Jae Goodman, chief creative officer and co-head of CAA Marketing so elqouently states (quoted in AdWeek):

“From the beginning, he said, the judges followed these criteria: The work had to be high quality, have a powerful relationship to the brand, attract an audience and not be interruptive, and be entertainment in its form and not just entertaining in its effect.

“The Displaced,” which immersed the viewer in the lives of three child refugees, was extraordinary both as an editorial and a marketing piece, said Goodman. Rather than describe its power, he urged the journalists assembled to watch it for themselves, but he did say that it satisfied one criterion in particular—the brand connection.

“This is a piece of entertainment content that moves the brand and the business that created it forward,” he said.”

Wowza. How’s that for journalism? It is high quality, but it’s branded content, meant to build a brand connection (here with Mini, GE and Google).

Why do I care? Does this matter?

I think it does matter, and I care because the future of our journalism, our advertising and our entertainment (and education, and enlightenment…) are being built now, and when you get your peanut butter in my chocolate and call it journalism, you’ve gone a bit too far. As John Oliver has pointed out, “Ads are baked into content like chocolate chips into a cookie. Except, it’s actually more like raisins into a cookie—because nobody f---ing wants them there.”

I have no problem with brands making content, obviously, because I promote it all the time. I have problems when this is hidden, or when someone really important (like the NY F-n Times!!!) pretends that it’s just another form of journalism. There’s a lot of ethical standards built up around journalism, and you’d expect our leading US paper to at least pretend to follow them. But in fact, the NYT is probably the most egregious rule-breaker here of all.

As I’ve shown in many of my branded content lectures, the NYT T Brand Studio – a relatively new entity at the NYT, built to work with brands on “native content” has been up to these shenanigans for awhile.

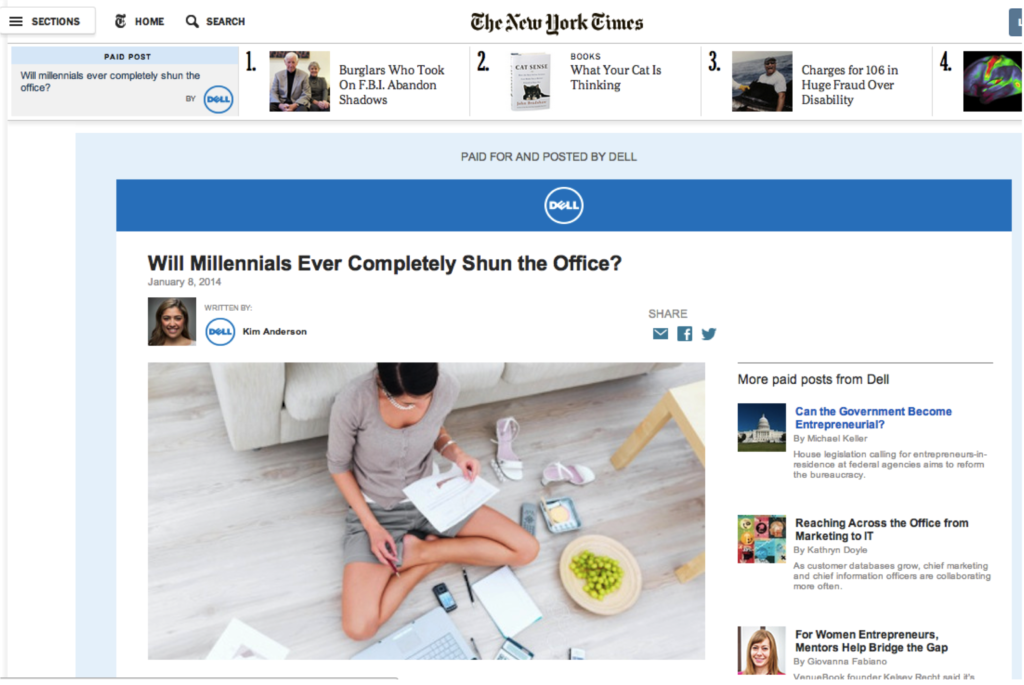

Here’s a photo of one of their earliest efforts:

Early Branding

Note that you can easily tell that it’s sponsored content. Well, that didn’t go over so well with advertisers, as was soon reported in AdAge:

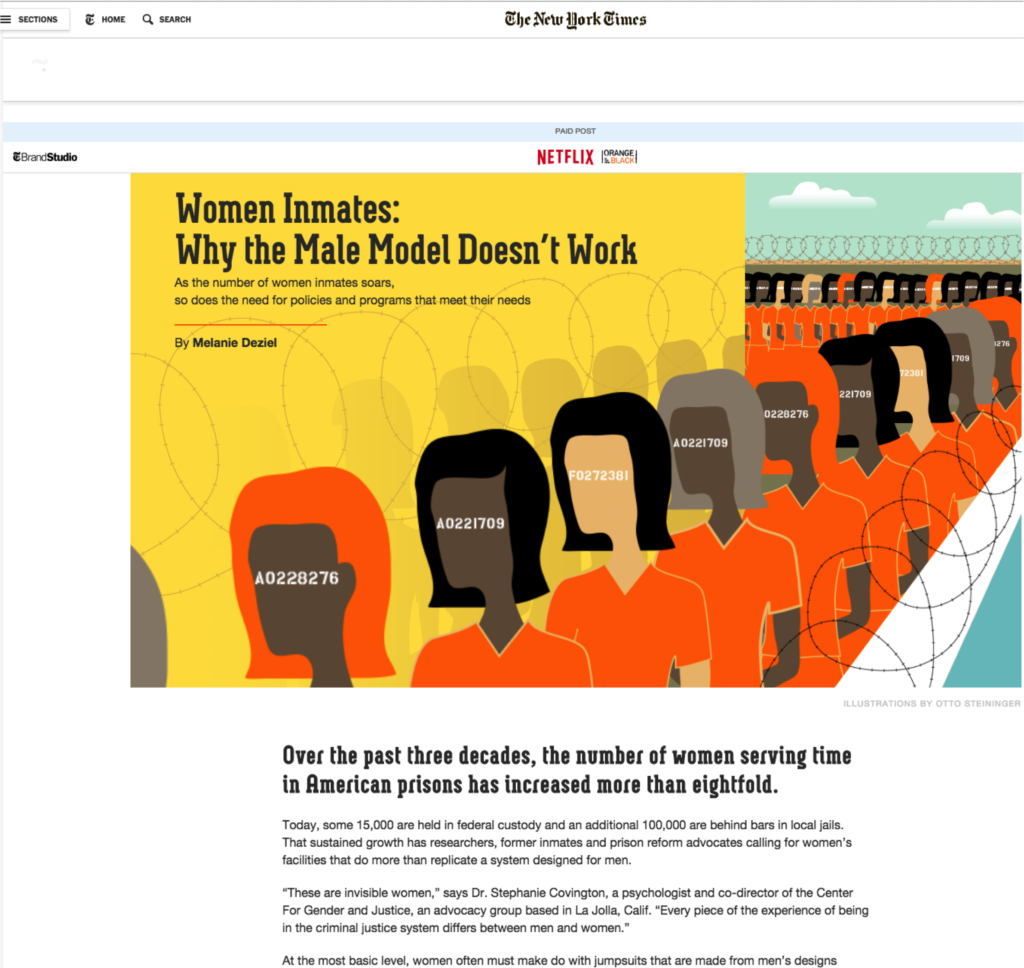

So then they came up with a new format:

Note here that the branding is much smaller. You could almost not notice that this great article on women in prison is really an ad for Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, which is how it becomes “native” or icky… Remember, this isn’t journalism. As the NYT T Brand Studio says on their home page: “We create and distribute insightful brand content and experiences that shape opinion.” It may shape opinion, but it’s still an ad.

Now they just come out and say that they’re VR story sponsored by Mini is journalism. But it’s not. It’s an advertisement. It may be cutting edge, and it may be important, and it is likely the future, but can we please just call is what it is?

In the meantime, if you want to watch some good films that are clearly branded content, and not journalism, and are honest about it, watch some of my client’s films here or here. Oh, and that’s an advertisement I just wrote, not journalism.